The Big Picture

- Hitchcock’s favorite film is

Shadow of a Doubt

for its true, character-driven portrayal of a family in Northern California. - The movie’s brilliance lies in the twisted character arcs of Uncle Charlie and young Charlie, with a morally ambiguous ending.

- Hitchcock defied the Hays Code with Shadow of a Doubt by exposing the dark underbelly of small-town America’s innocence and moral failings.

When asked “What’s your favorite Alfred Hitchcock film?”, there are several answers one may give. In terms of popularity, the current consensus seems to have landed on two particularly outstanding choices – the perennial horror classic Psycho, and the former Sight and Sound Greatest Film of All TimeVertigo. Yet if you pose this question to the Master of Suspense himself, his answer might surprise you. It’s not the two aforementioned classics, North by Northwest starring his favorite actor Cary Grant, Rear Window, or even Notorious – it’s Shadow of a Doubt, a lesser-known title from 1943.

So why did Hitchcock love Shadow of a Doubt so much? The iconic director gave many interviews during his lifetime, but he didn’t expand much on why he favored Shadow of a Doubt (he even once refuted the notion in his epic week-long sit-down with François Truffaut). In a 1972 interview with Dick Cavett, he gave three curt reasons: one, that “it was true”; two, it was a “character picture”; and three, that “it was a family in a Northern California town.” This last part was corroborated by his daughter, who said “[Shadow of a Doubt] was my father’s favorite movie because he loved the thought of bringing menace into a small town.”

From these brief notes alone, we get a glimpse at all that makes Shadow of a Doubt great – based loosely on the real-life serial killer, “the Gorilla Man,” it’s a movie of unconventional character trajectories that exposes the naïvety and darkness of picture-perfect Americana. It’s arguably his first truly twisted film, with an ending so seemingly upstanding yet cleverly dark that it outsmarted the puritanical Hays Code censors of the time.

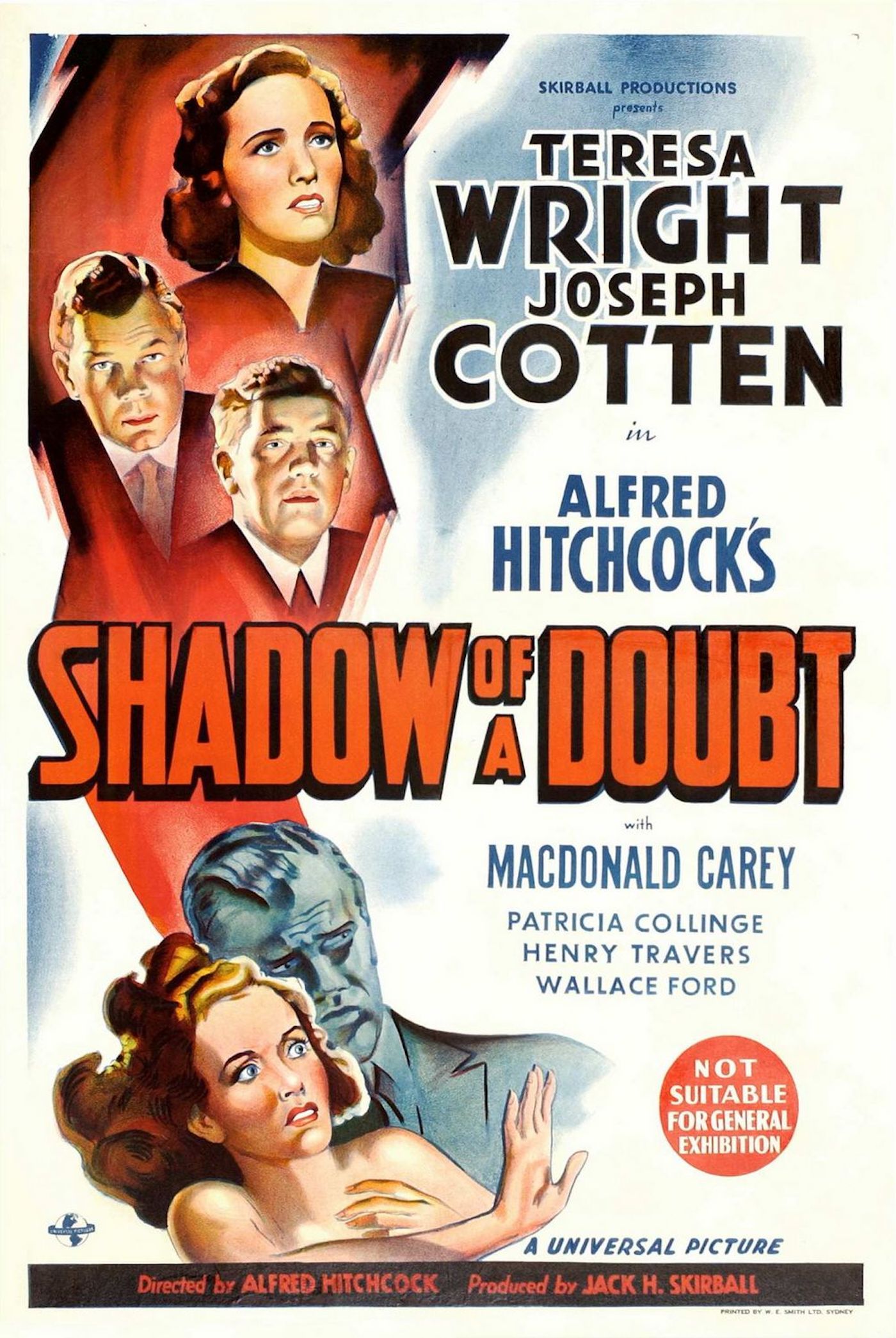

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

A teenage girl, overjoyed when her favorite uncle comes to visit the family in their quiet California town, slowly begins to suspect that he is in fact the “Merry Widow” killer sought by the authorities.

Release Date January 15, 1943

Cast Teresa Wright , Joseph Cotten , Macdonald Carey , Henry Travers , Patricia Collinge , Hume Cronyn , Wallace Ford , Edna May Wonacott

Runtime 108 Minutes

Writers Thornton Wilder , Sally Benson , Alma Reville , Gordon McDonell

What Is ‘Shadow of a Doubt’ About?

Shadow of a Doubt tells the story of two Charlies. Hitchcock begins the film with Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten, frequent Orson Welles collaborator), a rather odd and creepy adult man, lying on a bed in New Jersey. Being followed by two detectives, he decides to take a trip to Santa Rosa, California. In Santa Rosa, an oblivious, innocent teenage girl also named Charlie (Teresa Wright) is lying on her bed, hoping for some excitement to come into her life. A telegram arrives to tell her that her favorite Uncle Charlie is visiting. The two relatives reunite joyfully, but suspicious clues soon reveal that something’s afoot with Uncle Charlie. As one of the detectives and eventual love interest Jack Graham (Macdonald Carey) arrives to investigate, young Charlie discovers a horrible truth about her uncle. When Uncle Charlie decides to stay and wins over the townsfolk, only young Charlie and Jack are left to stop him and his nefarious ways.

Shadow of a Doubt was co-written by three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Thornton Wilder, Sally Benson, and Hitchcock’s wife Alma Reville. In the book Hitchcock by Truffaut, Hitchcock cites Wilder’s serious participation when he was still looked down on in America as why he regards this film fondly. Shadow of a Doubt was an instant hit and won effusive praise by critics. Contemporary reappraisal is even kinder; David Kehr of Chicago Reader calls it “Hitchcock’s first indisputable masterpiece.” One can see where that angle is coming from; while Hitchcock’s only Best Picture winner Rebecca is nearly flawless, it is largely a drama limited by Hitchcock still learning how to work with a Hollywood studio for the first time. In Shadow of a Doubt, Hitchcock gets to flex his genre muscles and test the dark thrills he later perfected. Even though he is largely limited to a single house, Hitchcock was able to transform that ordinary domestic setting into a wild and effective display of cinematography, with strong lines, stark shadows, and precious Dutch angles.

Why ‘Shadow of a Doubt’ Is Hitchcock’s Favorite

Among the three reasons given by Hitchcock, the second and third explain why this movie is so effective. Hitchcock calls this film a “character picture,” and while he has made many more films with great character arcs, none are arguably as perverse and dastardly as the two Charlies. The brilliance of Shadow of a Doubt is that, at least contemporarily, there is zero mystery as to whether Uncle Charlie is a criminal or not. Hitchcock starts the film with him; he is creepy as hell upon our first glimpse. Instead of the classic villain arc of slowly revealing their true colors, Uncle Charlie’s arc is a reversal – he starts the film in that odd, creepy state, and gradually wins over the Santa Rosa townsfolk with his charisma. By the end of the film, as he commits some of his biggest crimes, he is almost statesmanlike in his popularity. This makes the film’s trajectory truly wicked as the odds are increasingly stacked against young Charlie – as Uncle Charlie mesmerizes the town, she and her new detective boyfriend are the only people left who know the dark secret. Even with the truth on young Charlie’s side, her fight is increasingly futile, and with how the film ends, publicly unmasking Uncle Charlie is of no use. That truly has the power to drive anyone insane.

Related

Related

Alfred Hitchcock Never Got To Make His Gory Serial Killer Horror Movie

The visionary behind ‘Psycho’ almost had another envelope-pushing film, but it was too disturbing…

Young Charlie’s arc, on the other hand, is a classic coming of age, but tinged with Hitchcockian flavor. While women protagonists are common in Hitchcock’s filmography, a teenage girl is rare. This means young Charlie isn’t characterized by Hitchcock’s sexualizing male gaze and fetishistic obsession with blondes. Instead, she loses her innocence not physically, but psychologically. Hitchcock deflowers her by giving her the eternal torture of being the only person who knows Uncle Charlie’s secret. The ending is morally ambiguous in this nasty and heartbreaking way that only conjures respect for Hitchcock’s mastery. In clever defiance of the Hays Code, even when justice is “achieved” by strict Code terms, Hitchcock has sneaked in an unhappy, unresolved ending. These two character arcs, mirroring each other from light to dark (or vice versa), show the ingenuity of Hitchcock and his co-writers’ dramaturgy, even when the dialogue appears plain. As Hitchcock pointed out in his Truffaut interviews, “What it boils down to is that villains are not all black and heroes are not all white; there are grays everywhere.” That perfectly sums up the greatness of this film.

Alfred Hitchcock Defied the Hays Code With ‘Shadow of a Doubt’

Image Via Universal

Image Via Universal

As for the third reason provided, Hitchcock corrupted not just young Charlie but the town of Santa Rosa, California. At the time of this movie, Santa Rosa’s population was only 12,000, and in Shadow of a Doubt, it looks like picturesque Americana. With the arrival of Uncle Charlie, almost like a dark angel from industrial, urban hell, Santa Rosa proves itself utterly inept at countering such a force. Instead, it helplessly falls prey to Uncle Charlie’s charms. As Hitchcock told Truffaut, the villain “even has the public’s sympathy.” Hitchcock exposes the innocence and gullibility of small-town USA, casting it strictly as behind-the-times and unable to keep up, as America plunges itself into the biggest war in history that, when it ends, would surely change the world irrevocably. Again, Hitchcock somehow outmaneuvered the Code during its heyday, when films were supposed to promote “the correct standards of life.” Hitchcock certainly depicted those standards, but showed how utterly inadequate they are and how they lead to moral failings.

Hitchcock had a mean streak; he had an obsession with exposing the perverse underbelly of human psychology. That he achieved it under strict regulations of the Code only makes Shadow of a Doubt a greater triumph. Shadow of a Doubt may not be his most colorful, vivid, or thrilling film, but there is something intimately wicked about its character work that makes it a perfect choice for the director’s proudest achievement.

Shadow of a Doubt is available to rent in the U.S. on Amazon.

WATCH ON AMAZON