Jorginho and Aaron Ramsdale were immersed in a game of tactical chess at Arsenal’s Hale End academy. The duo were pitting one half of the club’s under-15s squad against the other.

The Brazil-born Italy midfielder’s team had been tasked with playing out from a goal kick and working the ball into the opposition half, while England goalkeeper Ramsdale’s side had to press high and steal.

“Ramsdale’s team kept winning it and scoring, winning it and scoring,” says David Bridges, a coach developer for the Professional Footballers’ Association (effectively the players’ trade union in the English game), who helped the Arsenal duo complete a bespoke UEFA B Licence course last month.

“Me and my colleague Matty Joseph were on the sideline saying (to each other), ‘Look at the space in behind to go a bit longer. Just miss out that first press and make it easier’. We suggested it and he (Jorginho) said, ‘No, no, don’t worry’.

“He went back into the session, inverted both full-backs into central midfield and put the midfield pivot right next to the goalkeeper on the goal line. His team got out of the press four times out of the next four. We looked at each and went, ‘Wow, what just happened there?’.”

David Bridges works with Jorginho during a coach development session (Professional Footballers’ Association)

Bridges asked Jorginho to explain how he had solved the puzzle.

“He said, ‘I just took away what they were going after. They were marking one-versus-one, so by moving a player inside and another back, they didn’t know who to go with. I just disrupted things. Then it is about finding the spare man’. I help players like ‘Jorg’ with their messaging and their structure, but that was a real learning moment for me. You realise how quickly his brain must see the game in elite football.”

It is the part of his anatomy that has always set the 32-year-old apart.

Jorginho has started only seven of Arsenal’s 27 Premier League games this season but that cerebral quality is why manager Mikel Arteta is increasingly saving his legs for the biggest domestic and Champions League fixtures.

He played just 20 minutes across the 10 league games from late November to the start of February but his outstanding performances in subsequent victories over Liverpool and Newcastle United showed how sharply he thinks in the most intense games.

Arsenal signed him from London rivals Chelsea as a short-to-medium-term solution in January last year, after missing out on a younger, more expensive midfield target in Moises Caicedo, who went to Chelsea from Brighton the previous summer. At £12million ($15.3m at the current exchange rate), Jorginho has represented terrific value in his 42 appearances for the club.

Even when he is not playing, his influence can be felt.

When Arteta was serving a one-match ban against Aston Villa in December, Jorginho, who was among the substitutes that day but didn’t get on, spent the full first half standing halfway down the touchline, barking instructions and even calling a couple of team-mates over during stoppages in play.

“He was our coach on the pitch,” says Antonio Gagliardi, who was the Italy national team’s chief analyst from 2010 until 2022 and now continues working with his old Italy boss Roberto Mancini as an assistant coach on his Saudi Arabia staff.

“It was beautiful to have this kind of player, as it is difficult to communicate from the bench during a game with the distance and the (crowd) noise. He understands pressing very well, so he would be shouting, ‘Go to the right!’, ‘React now!’.

“Along with (veteran central defenders) Giorgio Chiellini and Leonardo Bonucci, I spoke a lot with him as he understood a lot of tactical principles and concepts. We spoke with him before every game.

“Against Belgium in the (Euro 2020) quarter-final, he was very important as his role was to mark Kevin De Bruyne during our high pressure while watching the other players around him. He did it so well. After the first half against Spain in the semi-final, we changed some movements as (then Spain manager) Luis Enrique surprised us by using Dani Olmo as a false nine. In the dressing room, we spoke with the leaders to change because the game we had prepared was different.

“He understands everything very quickly, but importantly he also has the skills to communicate. Of all our players at those Euros, he is one I think will become a coach.”

Gagliardi cites the ‘triangle’ of Jorginho, Marco Verratti and Lorenzo Insigne as the backbone of Italy’s triumph in that tournament, as their abilities allowed Mancini to transition to a possession-based, high-pressing philosophy.

“Verratti is maybe a playmaker, maybe a No 8 and maybe a No 10. Mancini decided to put him very close to Jorginho,” says Gagliardi. “We used the positional structure of 3-2-5, with the two midfielders both playmakers. That was the secret of Italy, as we were a very difficult team to press, with Bonucci also as a playmaker and Insigne not being a traditional winger.

“Jorginho is very smart at understanding the situation. In build-up under high pressure, he quickly recognises the free player and plays as a third man, or when he was being marked man to man he was intelligent to leave the space for someone else.

Jorginho played a key role in Italy’s Euros win three years ago (Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images)

“Mancini’s assistant Fausto Salsano was the first one to say it I believe, but we all called him ‘The Professor’, because he knew every time what he should do with the ball.

“He is a facilitator. It may be simple passes, but they are the ones that earn others space and time for a line-breaking pass. It will not be easy for a player like Jorginho with his physical qualities in the future, but there will always be a space for a player with his intelligence.”

Jorginho’s physical limitations have seen him mocked at different points in his Premier League career since arriving at Chelsea with new manager Maurizio Sarri from Italian club Napoli in the summer of 2018. A video of him being outrun by a referee brought derision on social media and he became a lightning rod for Sarri’s early struggles at Stamford Bridge.

He has, though, repeatedly shown the strength of character to overcome the doubters. At the end of his Chelsea debut season, he won the Europa League and in a glittering 12 months from early 2021, he added the Champions League, the Euros with Italy, the European Super Cup and the Club World Cup to his collection, which led to him being voted UEFA’s men’s player of the year for 2020-21.

Another Italian who knows how to overcome perception in English football is Gianfranco Zola.

The diminutive forward joined Chelsea from Serie A’s Parma in 1996 with some questioning whether he would be able to cope in the rough and tumble of the Premier League, but he excelled across his seven seasons to the extent that in 2013 he was voted Chelsea’s greatest ever player.

Zola was part of Sarri’s coaching staff when he took over at Chelsea in 2018 and attempted to implement the high-tempo, short-passing vision of his Napoli days.

“(Signing) Jorginho was one of his conditions when he (Sarri) first got the job,” Zola tells The Athletic. “He was the first player he asked for, as he knew that if he wanted to put in place his own structure of football, Jorginho was a key element.

“The criticism was the same thing they said to me when I first came — the game was too physical, I wasn’t going to cope with the situation, this and that. But when you’re a smart player, you can find a way to be successful.

“It also depends on what the team want to do. If you want to play a physical game, go for second balls and rebounds, you have to have a different type. If you want the ball all the time and build up from the back, then Jorginho is one of the best interpreters of that.

“He has a very quick mind. Before he receives the ball, he knows already what to do.”

As a young player in the coastal town of Imbituba, on the southeast coast of Brazil, Jorginho made his first big move at 13 years old.

Even then, it was how he thought that stood out.

After impressing at a trial, he was signed by AFEG Guabiruba, who had received investment from a group of Italians intending to develop players to take to Europe — which is why the club were known as Guabiruba Calcio at that time.

Jorginho was nicknamed ‘Seco’, because of his slight frame. It translates as ‘dry’, but it was used to say he was so thin there was not a bit of fat on him.

“Today, defensive midfielders have to be physically imposing more than technical. That wasn’t him but he always put so much effort in,” says Marcio Cesari, one of his former coaches. “If everyone had to do 10 sprints, he’d do 15. If they had to work on a particular skill for 10 minutes, he’d stay out there and do more. He wanted to overcome his body, his physique. He was really thin but his technique made up for it.”

Jorginho with his Guabiruba team-mates (AFEG Guabiruba)

Jorginho was one of 70 players based there, sharing a dormitory with 30 or 40 other hopefuls. The experience toughened him, as did playing in the Santa Catarina state championship via Guabiruba’s partnership with local senior club Brusque.

An Italian coach named Mauro Bertacchini arrived armed with a training methodology that is still employed at Guabiruba today, but also precious few golden tickets to move to Europe. He made the final decision on which of the players were good enough and, while several went to play in the Czech Republic, Jorginho went to Hellas Verona in Italy.

In interviews, Jorginho has described those two years at Guabiruba as the most difficult of his life, due to the stale food, crowded rooms and cold showers in winter.

“When he went to Verona, his agent Alessandro De Blasi owned his economic rights. Guabiruba didn’t earn a penny. Even when he went from Napoli to Chelsea, only Brusque received money,” Cesari claims.

“Jorginho has never returned to Guabiruba since going to Italy. It makes me sad. We are proud to have played a part in his development, helped him realise his dream. Now he has conquered the world and is famous wherever he goes. We just want him to acknowledge where he came from. Or maybe just come and give a talk to our youngsters.”

As an 18-year-old Jorginho was sent on loan to fellow Italians Sassuolo in October 2010 to compete in the Viareggio youth tournament against the other top academies from the country. They reached the quarter-finals, but he was taken off after 70 minutes as they were lost to Juventus. “There was flooding, so the pitch was impassable,” says Pedro Costa Ferreira, a Sassuolo team-mate in those days.

Ferreira remembers Jorginho as looking like he was heading to school rather than training because he always carried a backpack. “Perhaps more than the others he paid for his physical appearance, given that he couldn’t play his way. We saw a player different from the others because of how he read the play before the others. It was like he knew exactly where the ball would fall.”

Jorginho was still judged not ready to play in Serie B, Italian football’s second division, with Verona and spent the 2010-11 season on loan at fourth-tier neighbours Sambonifacese.

Their manager Claudio Valigi, who had won the Serie A title as a player with Roma in 1982-83, was tipped off about Jorginho by former Italy midfielder Giuseppe Giannini.

“He was the player I adored,” says Valigi. “He was the perfect architect for building play, a continuous reference for his team-mates. He catalysed the game like a magnet. The more balls he played the more excited he became, but he was always clear-headed. No negative emotions showed through and he was recognised as a leader by everyone.

“Jorg is a beautiful example to study for young people that talent must be understood. That is what struck me most: his hunger to emerge. He was street-smart, like a Neapolitan from the Spanish neighbourhood, and that made him grow quickly.”

When he returned to Verona for the 2011-12 season, he either did not make coach Andrea Mandorlini’s squad at all or was an unused substitute in 11 of the first 15 Serie B games. It took a second-half injury to Niccolo Galli against Bari in the November for Jorginho to assert himself as a permanent member of the starting midfield.

The following season, he was instrumental in their promotion to the top flight for the first time in nine years, starting 40 of the 42 league games.

“Giving the ball to Jorginho was like giving it to the bank,” says Domenico Maietta, who played behind him in defence for Verona until the midfielder’s 2014 move to Napoli. He was so intelligent. He did not have a big physical structure but he only needed one or two touches to play. If you played it to him really fast, it would still remain at his feet.

“He was the ‘regista’ of the team and tactically always took up a position that was justified. He became the filter in front of the defence which everything went through.

“Before everything, his first quality is his intelligence. His head is a football head. He is a mix of Andrea Pirlo and (1994 World Cup-winning Brazil captain) Dunga, if I can put them together like this. In the season we got promoted with Verona, he was the lighthouse in central midfield.”

Roberto Bordin, now manager of Serie C club Triestina after spells in charge of Sheriff Tiraspol of the Moldovan league and Moldova’s national team, was an assistant at Verona during Jorginho’s four years there as a first-team player.

“His brain is up there with the best midfielders of the last generation,” says Bordin. “His mentality was super-professional, and he showed he could play in a 4-4-2 as well. He adapted to every kind of style and system. After we trained a new system for an hour and a half, he would ask me to train alone with him so he could improve and find new solutions. I would put silhouettes (dummies) around the pitch as potential opponents and we would work on different passages of play.

“We trusted his choices during the game. He listened to our messages but a lot of times I said to him, ‘Do what you think is right’, because he was very intelligent and could change the game on the pitch.”

Following that promotion in the summer of 2013, Jorginho took to Serie A as if he had been playing in it his whole career. He scored five goals in a run of four games in the September and October (all but one of them penalties) and in the January window, a month after he turned 22, Rafael Benitez signed him for Napoli. And it was when Sarri succeeded Benitez in the summer of 2015 that Jorginho found a manager whose view of football aligned perfectly with his.

Football analytics company Soccerment has found that, over the past seven seasons, the Napoli side of 2017-18 played the quickest passing football across Europe’s top five domestic leagues, with 11.7 passes per minute in possession.

Sarri is famed for almost exclusively coaching his teams to play one and two-touch combinations during build-up. Jorginho excelled at the base of the midfield as Napoli twice came close to winning Serie A, falling five points short in 2017 and four a year later.

Sarri only lasted one season at Chelsea despite winning the Europa League, reaching the Carabao Cup final and finishing third domestically, and his brand of football split opinion among the fanbase. There is an irony that Jorginho’s critics often advocated for Declan Rice to be signed as his replacement, as the young Englishman was seen to possess the all-action abilities the older Italian lacked.

They are now in the same title-chasing team at Arsenal. And not just that — after joining from West Ham United last summer, Rice said Jorginho was the player whose quality had surprised him the most and that he had been trying to learn from him in terms of how he controls games.

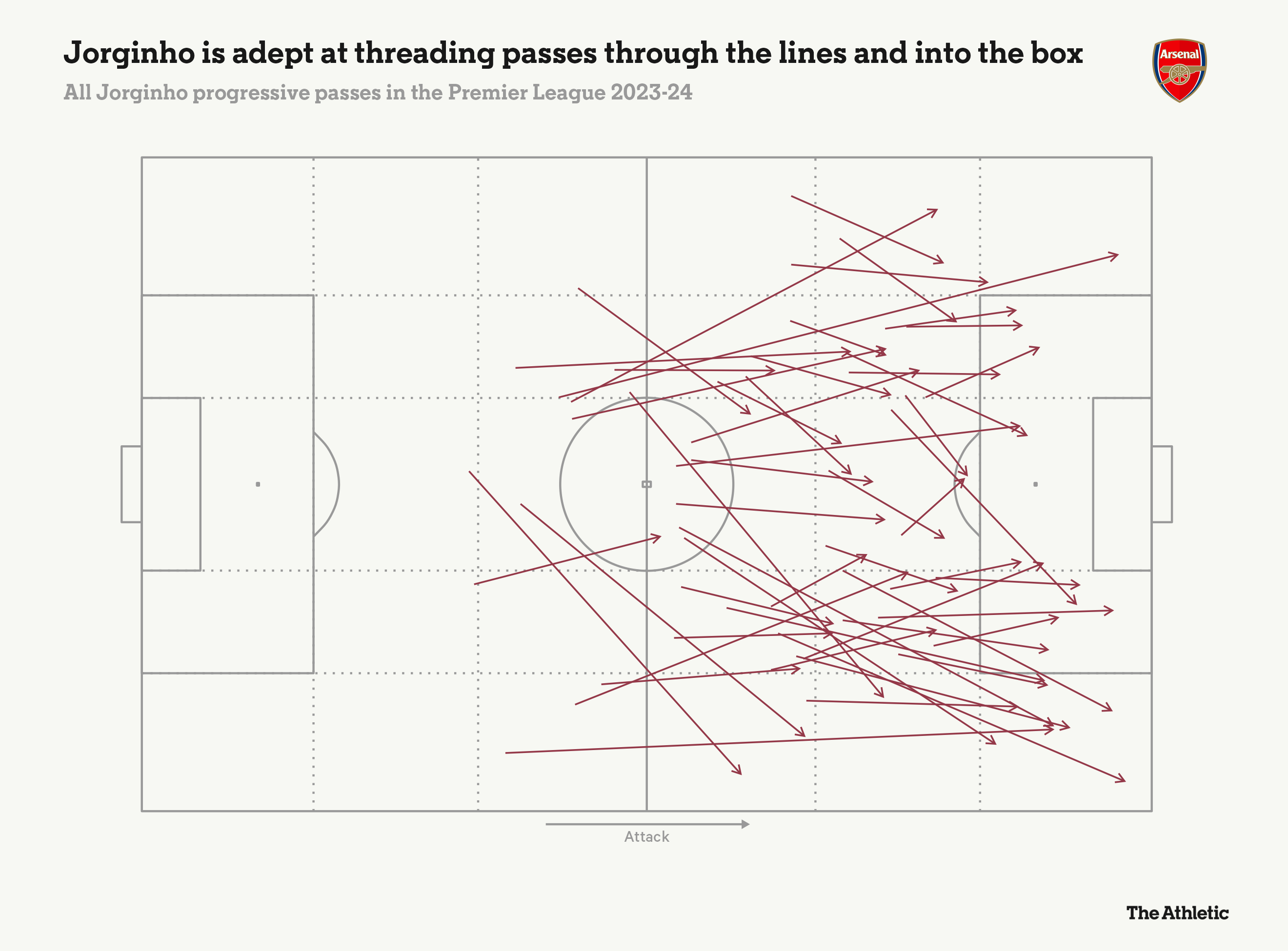

Looking at turnover rate, which is calculated by dividing a player’s touches by the number of times they lose possession, Jorginho has been the Premier League’s third-most secure midfielder on the ball this season, at just 10.2 per cent. He does not just keep possession for his team, though. He has also been the division’s best midfielder when it comes to completed progressive passes — defined as one that moves the ball 25 per cent closer to the centre of the goal.

Although Jorginho has played fewer league minutes (659) and therefore had fewer touches than his rivals, who have all played more than 1,500 minutes, his average of 7.1 progressive passes per game this season even beats Manchester City midfielder Rodri, who is next best at 6.6 per 90 minutes.

High-pressing, possession-heavy teams have proliferated in the past decade but while the elite clubs become increasingly homogenous in style, football has become more focused on one-v-one battles, with players expected to cover large areas of the pitch themselves.

GO DEEPER

Jorginho exclusive: Arsenal ‘energy’, no-hop penalties, love for Havertz, knowing strengths

In Jorginho’s most difficult moments, it is that type of game that has exposed his weaknesses. It is no surprise his best period at Chelsea came when he was playing alongside N’Golo Kante, one of the best defensive midfielders of the modern era. In a similar way now, his pairing with Rice — a powerhouse — covers up his flaws and allows him to be the brains of the Arsenal midfield.

With the Champions League and Premier League still to fight for over the next three months, Arsenal will need Jorginho’s brain more than ever.

Additional reporting: Jack Lang and Thom Harris

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Dan Goldfarb)