The Amazon may experience unprecedented wildfires this year that could severely damage its vital ecosystems, experts have warned.

Record-high temperatures, severe drought conditions and the El Niño weather phenomenon have combined to make the Amazon “more flammable, “Bernardo Flores, a researcher at Brazils Federal University of Santa Catarina, told Live Science. Experts monitoring conditions in the Amazon are now concerned there will be a big uptick in fires over the coming weeks.

“Climatic changes in the Amazon region are increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme drought events, which are happening in combination with heat waves,” Flores, whose recent work focused on the potential collapse of the Amazon, said. “These hot-droughts desiccate the forest soil and organic matter, allowing wildfires to spread deeper into standing forests.”

The Amazon Rainforest is among the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. It is home to 10% of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity and plays a vital role in stabilizing both local and global climates. But the region is under increasing threat from warming, deforestation, droughts and wildfires.

Most wildfires in the Amazon are the result of humans burning recently deforested areas. “In some of the places where deforestation is going on, they cut the forest just before the dry season so that they can burn and clear the land in the dry season,” Dolors Armenteras Pascual, an ecologist and professor at the National University of Colombia, told Live Science.

“Once the forest is converted it is used for agriculture. Those pasture fires can enter the standing forest, and that’s when there is a degradation process in the standing forest,” she said.

Related: Catastrophic climate ‘doom loops’ could start in just 15 years, new study warns

Scientists monitor conditions in the Amazon in real time and use these data to create fire risk models predicting when and where wildfires are likely to occur weeks and even months in advance.

Two such models are NASA’s GEOS S2S (subseasonal to seasonal) forecast and Land Data Assimilation System (LDAS), said Benjamin Zaitchik, a professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins University. Zaitchik and his team use these models — along with remote sensing satellites — to monitor ongoing weather conditions, such as temperature and rainfall. Those data are then combined with measurements of soil moisture, groundwater, and vegetation conditions to forecast a given region’s fire risk in the near future.

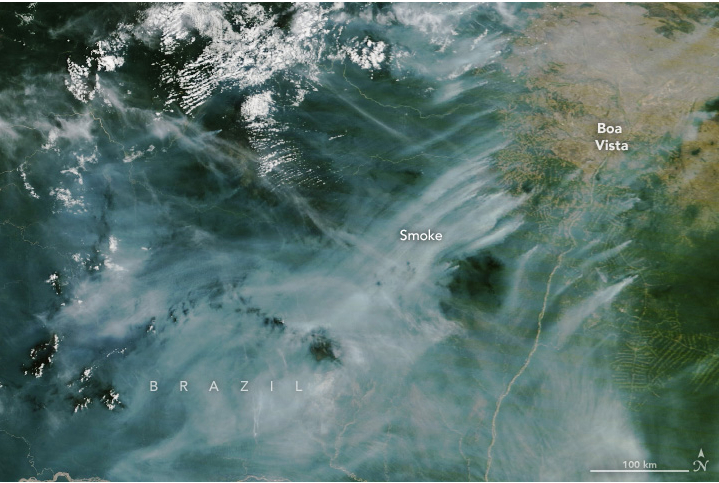

Smoke from wildfires sweep across the Brazilian state of Roraima in this image taken in February. (Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey)

Late last year, a team from Brazil’s Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN), led by Liana Anderson, reached out to Zaitchik and his colleagues and asked them to help forecast the Brazilian Amazon’s fire risk.

“The monitoring and forecast tools were quite clear that there was elevated fire risk across much of the Amazon throughout the (Northern Hemisphere) fall and winter seasons,” Zaitchik told Live Science in an email. “This was in part due to low rainfall in sections of the Amazon, but it was even more strongly predicted due to high air temperature across the region.”

The northern Amazon fire season normally peaks in March. Forecasts for 2024 indicate that very warm and likely dry conditions will continue through to April

at least, Zaitchik added.

These predictions have already started to materialize. On Feb. 28, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research announced that a record-breaking 2,940 fires burned in the Brazilian Amazon in February.

The forecasting models may help governments and aid organizations get out in front of wildfires in the Amazon.

“The Amazon is a vast area, so any ability to preposition fire control materials can be very important,” Zaitchik said.

Similar forecasts from Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) show that fire risk in the Colombian Amazon is expected to increase in coming months as well. The Colombian government is currently working to position firefighters and aircraft in regions where fires are expected to blaze.

Looking further into the future, Flores says that wildfires in the Amazon are expected to increase in frequency and severity as a result of climate change. “Fire is a contagious process,” he said. “If nothing is done to prevent fire from penetrating remote areas of the Amazon, the system may eventually collapse from megafires and become trapped in a persistently flammable open-vegetation state.”