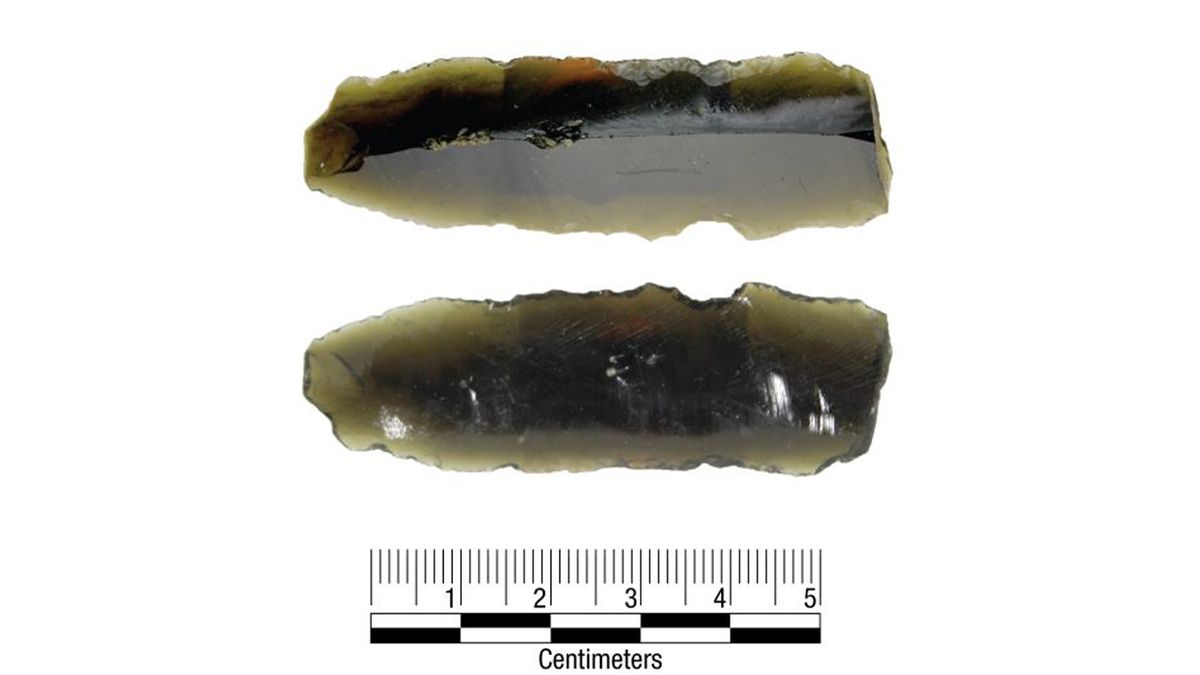

A greenish obsidian blade, believed to have been found on the Texas Panhandle, may be from the 16th-century expedition led by the Spanish explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, a new study suggests.

The sharp tool’s provenance is hazy, but a chemical analysis of the obsidian reveals that it came from the Sierra de Pachuca mountain range of Central Mexico, where many Indigenous people on the expedition got raw materials for cutting tools, the researchers found. It’s possible that an Indigenous person traveling with Coronado crafted the blade in Mexico and later discarded it in Texas, which could help determine Coronado’s exact route through the Lonestar State, the researchers said.

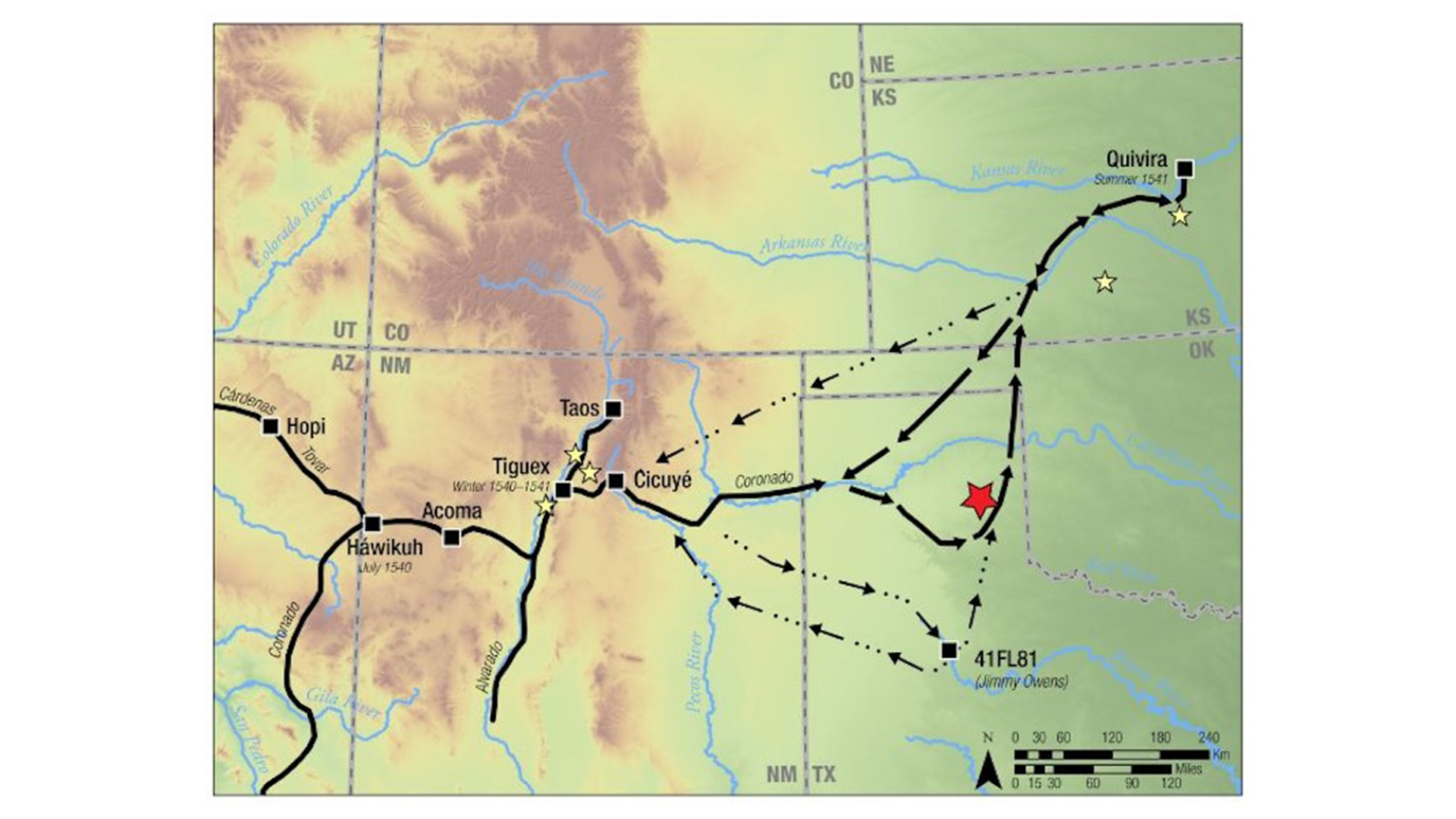

“Although Coronado’s exact route through the Texas Panhandle in AD 1541 is uncertain, current understanding suggests that it passed through or close to Mclean,” the researchers wrote in the study, published in January in the Journal of the North Texas Archeological Society.

Related: ‘Spirit mirror’ used by 16th-century occultist John Dee came from the Aztec Empire

The 2.6-inch-long (6.5 centimeters) blade belonged to Lloyd Erwin (lived 1920 to 1992), who began collecting Indigenous American and historical artifacts as a boy on his family’s ranch north of McLean. However, Erwin didn’t leave any archaeological notes describing the blade, so it’s unclear when or where he got it. But the study’s authors suggest that he likely found the blade on the Texas Panhandle, possibly around McLean, as he did many of the other artifacts in his collection.

According to common lore, Coronado and Spanish knights were sent by the king of Spain to look for the fabled gold Seven Cities of Cíbola. Nowadays, historians note that it was Antonio de Mendoza, Viceroy of New Spain (modern-day Mexico), who ordered Coronado to find the rumored city; instead, Coronado’s expedition journeyed to modern-day Kansas before returning empty handed. And Mendoza may actually have tasked Coronado with finding a route to Asia, Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, a husband and wife team who are research associates at the Latin American and Iberian Institute at the University of New Mexico, told Live Science. Neither of the Flints, who wrote “A Most Splendid Company: The Coronado Expedition in Global Perspective” (University of New Mexico Press, 2019), were involved with the new study.

The expedition of at least 2,800 people journeyed across Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Oklahoma and Kansas from 1540 to 1542. Because obsidian blades are brittle, they were often discarded. “We suspect that this blade represents a hafted knife or razor carried northward,” the researchers wrote in the study.

A map of northern New Mexico and the southern Great Plains showing the reconstructed paths of the Coronado expedition. (Image credit: SMU)

“This small unassuming artifact fits all of the requirements for convincing evidence of a Coronado presence in the Texas panhandle,” study co-author Matthew Boulanger, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University, said in a statement. Boulanger conducted the study alongside Charlene Erwin, the daughter-in-law of Lloyd Erwin.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, a non-invasive technique that determines an object’s elemental composition, revealed that the blade is “wholly consistent with obsidian from the Sierra de Pachuca source in Central Mexico,” about 55 miles (90 kilometers) northeast of Mexico City, the authors wrote in the study.

Indigenous people, including the Nahua, used obsidian to make tools until shortly after the Spanish conquest, at which time they switched to iron, the authors wrote. There was no known evidence of a trade network between the Indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and the Texas Panhandle at that time, the researchers noted, suggesting that the blade didn’t come to Texas through trade, but through an “entrada,” or a Spanish expedition into “new lands.”

While there were other entradas in this region in the 16th and 17th centuries, Coronado’s was the largest and had the most warriors, so they were more likely to carry these obsidian blades, the researchers wrote.

But, given the uncertainty of the blade’s origins, it’s hard to say for certain whether it came from the Coronado expedition, the Flints said.

“If it was really found there [in McLean], it helps confirm what most of us think is already that corridor” where the expedition traveled, Shirley Cushing Flint told Live Science. “Which is nice. You know, we don’t have a piece from there.”

Richard Flint told Live Science the find “would be more convincing if there were other objects, not necessarily the same kind, but other ones that might be also associated with the Coronado expedition.” Such a discovery, said Flint, could offer better evidence that Coronado passed through hundreds of years ago.