The touchline is pantomime; remember that and you won’t go far wrong. Whether on match day or otherwise, much of what a manager does is deliberate and rehearsed, usually designed to get a message across, most often to their players and supporters, sometimes to officials and occasionally to the opposition. It is about grasping responsibility, showing they’re alongside the team and demonstrating authority.

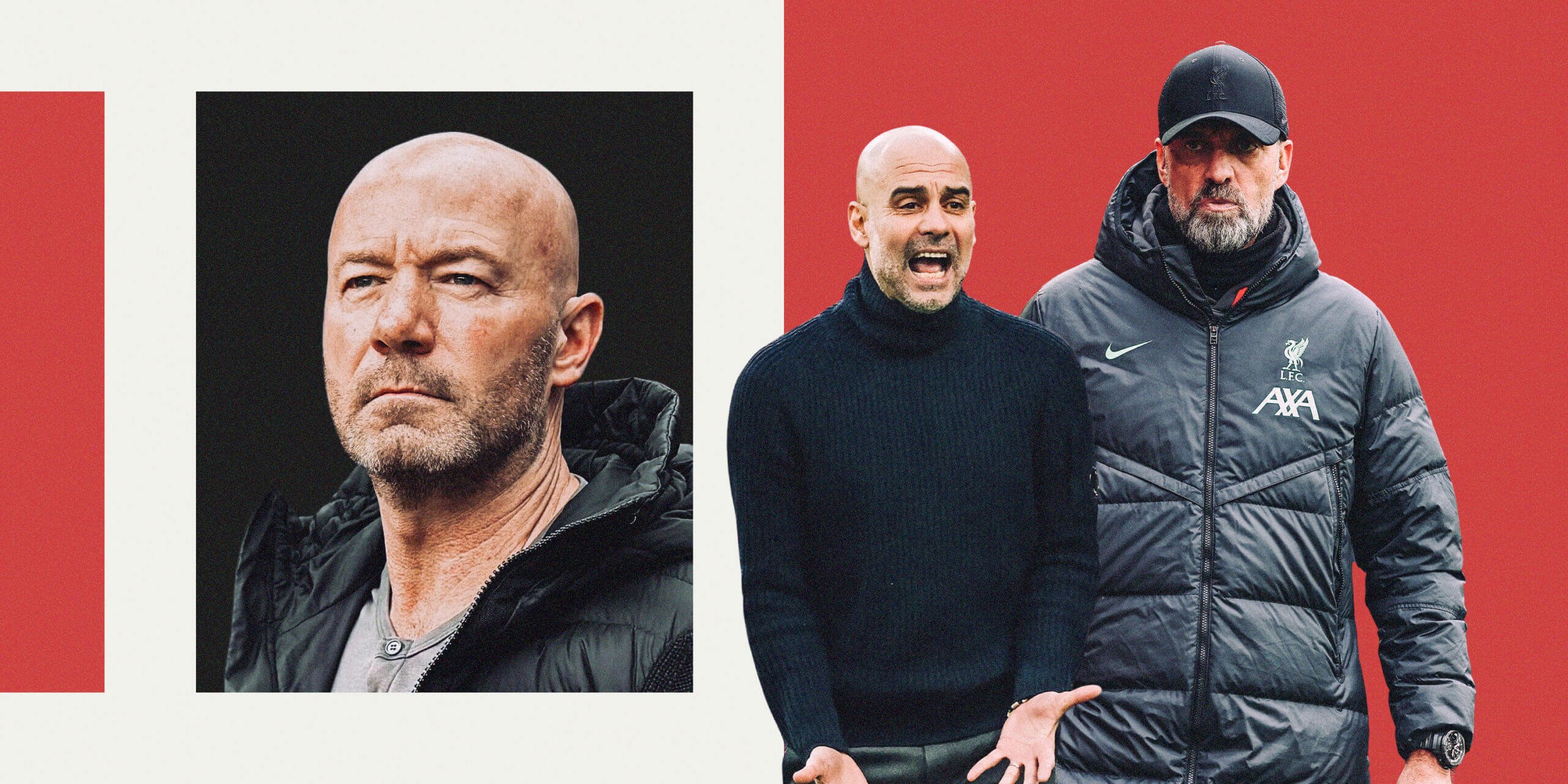

This is not to say that Jurgen Klopp or Pep Guardiola will be knowingly theatrical when Liverpool and Manchester City face off this weekend, when the German pumps his fists and the City manager gesticulates wildly. Nor if Mikel Arteta races down the touchline should Arsenal beat Brentford the evening before. Football is about emotion and feeling and I’m sure that’s all genuine, with everything heightened in this fascinating, three-pronged title race.

As a fan, I would love to see that kind of passion from my manager. I’d be thinking, “He cares about the club and team as much as we do, look at what it means to him.”

When I go through the list of managers I played under, none particularly behaved like that, even if people like Kevin Keegan, Kenny Dalglish and Sir Bobby Robson were all passionate, obsessive men. There was more reserve in football back then, certainly in public and the same applies to life in general. Sir Bobby believed in the dignity of his role, that he had to set standards; I can recall him saying of Arsene Wenger: “Some people around here need to learn how to lose.”

More than ever, the Premier League is a show — a strand of entertainment, more overtly emotional and constantly expanding — and managers and coaches are frequently showmen with big personalities. We swooned at Jose Mourinho when, as the manager of Porto in 2004, he gambolled alongside the pitch at Old Trafford during a Champions League tie.

The Kop hails Klopp when he thumps his chest at them after Liverpool matches and, as he said recently when asked about Arteta and the notion of over-celebrating, “You do what you do for yourself and your people and what the outside world thinks about it I couldn’t give a s*** to be honest,” which is absolutely fair enough. Liverpool vs City is a monster of a game in the context of this season and adrenaline does strange things to people.

Klopp and Guardiola can be expected to put on a performance this weekend (Visionhaus/Getty Images)

This article is more about the relationship between manager and team during games and how much pantomime that contains. Arteta, for example, is exhausting to watch, a whirling dervish constantly urging his players to move forward or drop back, as if conducting their every move. Do the histrionics and constant hand-waving work? Results suggest so, although I’m not convinced about how much of it will actually sink in when the game is moving, the pace is blinding, and the atmosphere electric.

Again, I would say it’s more about being seen and being part of it, showing he’s experiencing every peak and trough over 90-plus minutes and ramming home general instructions — broad brushstrokes — which, to most players, would be pretty engrained and automatic anyway. It’s what you work on all week at the training ground, practising every feasible scenario that crops up.

That emotion is genuine, but the setup around it is artificial. Arteta puts himself front and centre, but Ange Postecoglou and Eddie Howe do the same with Tottenham Hotspur and Newcastle United, albeit in a very different way. Neither Postecoglou nor Howe are demonstrative — quite the opposite — but they rarely budge from their technical areas. It is not a coincidence. As leaders, they put themselves front of shop, there to protect their players and soak up any flak.

Howe often talks about doing his best to remove himself from emotion, to put the noise and mayhem into a little box and ignore it, to make his decisions in the coldest, most clinical way he can. It must be difficult sometimes because football can be chaotic and messy, where all your meticulous preparations can be upended by one careless concession or a mistake.

Does an emotional game need a decision-maker who can feel and reflect that emotion or one who can deflect? I don’t know if there’s a right or wrong answer, but it’s an interesting question. Howe would probably argue that if a player glances over to the bench in the heat of battle and sees this calm, calculating figure looking back, it would offer reassurance — stick to the plan and we’ll be fine. Perhaps Arteta would say his lack of restraint is proof that he’s shoulder-to-shoulder with them, all for one.

To extend the analogy, do you want your general beside you in the fray, swinging his sword, leading by example, or do you want him standing at the back, removed from the action but coolly assessing the patterns of attack and defence and responding to them?

It was definitely pantomime season when I (briefly) had a stint as Newcastle manager in 2009, with a large dash of farce and tragedy thrown in. I didn’t think about how I would behave in advance, aside from wearing a suit and tie on the touchline. Some of the players were former team-mates of mine and it was important, I felt, to show things were different now, that I had to be aloof, separate, that there could be no favouritism.

Shearer, suited but stoic as Newcastle manager (Malcolm Couzens/Getty Images)

If anything, I took the Howe approach on the touchline, but that also reflected my personality. I wouldn’t have been one for going mad or throwing my arms around. What struck me was how the brain quickly becomes crowded; you have so many decisions to make, so many solutions to find, so many things you’re trying to think about and work out. It’s very difficult to keep your cool when it’s your neck on the line and then suddenly the referee makes a terrible, game-changing call…

It was approaching the end of the most toxic season in Newcastle’s recent history — I was their fourth manager, permanent or temporary, which tells its own story — and there was no semblance of togetherness. It felt like the whole place was spinning apart. I suppose I wanted to counter that, to portray a sense of control on the touchline, to offer an alternative scenario where everything was in hand and would be OK.

It wasn’t OK. Newcastle were relegated.

But that was how I went about it and, by and large, I felt like I got my messages across. On the outside, I was clear-eyed, stoic. Internally, I was molten. Against Middlesbrough, in our third-last game, I made a couple of substitutions when the score was 1-1, the changes worked, the team responded, we won 3-1 and it took everything I possessed not to f***ing run headlong straight into the Gallowgate End to celebrate. That isn’t much of an exaggeration.

In our next match, at Fulham, it went the other way. Sebastien Bassong was sent off when we were losing 1-0 and Howard Webb, the referee, disallowed an equaliser. We lost. I was absolutely raging inside, swearing and biting and clawing and fuming. I just about managed to swallow it, but I understand that staying in control is easier said than done.

Coaches are human and their minds can become scrambled like anybody else’s. There were rare occasions as a player when I would look across to the bench and think, “What the f*** is he going on about?”. It tended to be in those crazy moments when you’d been winning comfortably, the game is turned upside down and suddenly plans have been tossed out of the window and it felt like a trap door was creaking beneath you while a hurricane blew.

It even happened with the great Sir Bobby, who’d managed Barcelona, who’d managed England in a World Cup semi-final, who’d won trophies across Europe. What game it was is lost in the mists of time, but I remember him shouting instructions at me once and thinking, “I honestly don’t know what point you’re trying to make here.” Football is so quick and instantaneous that you don’t have time to understand, either.

I never worked under an Arteta kind of manager, someone manically cajoling, telling you exactly where to stand or exactly what to do. I’ve always been of the opinion that if you’re a good player, then you know that stuff anyway. If I felt I needed to drift out to the right wing or the left wing or even drop deep, I would do it myself. And as a captain, I felt I had the authority to tell my fellow players to do something. If it needed saying, I would say it.

Not everybody is like that, though. Some footballers are brighter than others. Some are needier than others. Some are more effective when they are given precise instructions and are forced to stick to them. Shouting, repeating, shouting again and reiterating straightforward messages might be the best way to get through.

What I wanted from my manager was to be led, to be guided. I wouldn’t have enjoyed being ranted and raved at from the touchline and I can’t remember it happening too many times. Why would I have hated it? Professional pride. You’re playing in front of thousands of people in the stadium and millions at home on television and you don’t want to be embarrassed. It might sound thin-skinned, but teams are delicate. Relationships hold them together.

Arteta is among the Premier League’s more active managers on the touchline (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

Mourinho doesn’t have a problem hauling somebody off 20 minutes into a match, which has always been viewed as the ultimate humiliation. Most managers wouldn’t do it or would wait until half-time. Jose would say he’s looking out for the team as a whole and if something isn’t working, then it isn’t working, but the risk is obvious, that the player who comes off complains to his mate and alienation snakes through the squad like a poison. Winning masks everything.

For me, being led meant being called over for a quiet word, or perhaps a shout and a bit of pointing, not a bollocking but simple guidance. Those things are important when a manager needs to change the team’s system or someone’s position or explain what the logic is when he brings on a substitute. That’s what you need but, again, almost everything he does will have been trained, honed or signposted.

In a wider sense, the pantomime aspect has always been a part of it.

I laugh when people get riled about things managers say in press conferences. When Wenger repeatedly claimed not to have seen the incident that led to an Arsenal sending-off, it wasn’t myopia and I’ll never accept it was serious, either. He might have been an extreme example, but one of the first rules of the game is never to attack your own in public. Or if you do, make it specific and very isolated. Laying waste to the group is almost always a last resort.

It was the same with Sir Alex Ferguson at Manchester United, a genius of a manager capable of dugout rages or pettiness when the cameras were rolling. Most of the time, he knew exactly what he was doing. He would circle the wagons around Old Trafford with the aim of boiling down one of the biggest clubs in the world to the smallest; only him and his players, them against the world, f*** everyone else. It was one of his greatest strengths.

Managers drop little bombs from time to time, inferring something without saying what they really mean. They might talk about decisions going against them in the hope it makes a flicker of a difference when the referee is presented with a 50/50 in their next match. They might praise a player from the team they’re playing. Liverpool’s Bob Paisley was renowned for giving opponents “a bit of toffee” in the hope it would sow confusion.

Why do they do those things? Managers walk a tightrope, on the one hand needing to maintain discipline, promote cohesion and show they’re in charge and, on the other, knowing that players are the very people who will keep them in a job, help them to win things and make them look better. On the touchline or off it, it doesn’t matter if they seem unhinged to the wider public because that is not who the pantomime is for.

(Top photo: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)