A meteorite allegedly exists in the Sahara that would make all the other meteorites look like pebbles. An object the size of a skyscraper, it was reported in 1916 by Western observers but then disappeared without a trace. Now, scientists in the UK have set out to solve the mystery with the help of radar data and elevation models.

The story sounds like something straight from the adventures of a young Indiana Jones. In 1916, French consular official Gaston Ripert, stationed in Mauritania (then under French control), reported to colleagues that he had witnessed an enormous meteorite in the desert outside the town of Chinguetti. After allegedly overhearing a conversation between camel drivers about an “iron hill”, Ripert embarked on a nighttime mission to the object with a local chieftain who either forbade him to bring a compass or blindfolded him, according to translations. The chief was later poisoned.

The secrecy was certainly warranted – if we believe the story – because Ripert’s accounts describe a meteorite that is so big he described it as an “iron mountain”. It was at least 100 meters (330 feet) long and 40 meters (130 feet) high. For comparison, the biggest known verified meteorite, called Hoba, is 2.7 meters (8.9 feet) across.

Ripert provided intriguing descriptions of this iron hill and even managed to chisel a fragment off, weighing about 4.5 kilograms (10 pounds), which scientists at the time declared a significant discovery. However, subsequent searches for the meteorite beginning in 1924 failed to find it. Ripert described it as nearly covered by sand, so it’s possible it is now buried beneath the sand of the Sahara.

Scientists have been intrigued for decades whether this iron hill actually exists. Now, in a new yet-to-be peer-reviewed preprint paper, Robert Warren, Stephen Warren, and Ekaterini Protopapa have proposed the means of determining once and for all if it existed and even where it may be found.

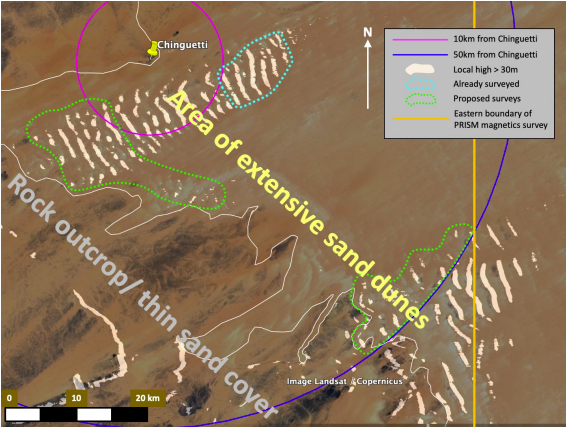

This is where the Chinguetti meteorite might be hiding.

Image Credit: Warren et al. 2024

The new work combined data from radars, digital elevation models, and interviews with camel riders to narrow down possible locations for this object. If it did exist, it would have to be covered by a dune at least 40 meters (131 feet) high, they posit.

They have requested magnetic data from the air by Mauritania’s Ministry of Petroleum Energy and Mines but its data was not made available to them. Still, the team thinks that a three-week survey should allow them to cover the area they believe hides the meteorite. They actually did investigate a small portion of the region by foot over three days without success.

“It is possible that the meteorite became covered by sand within a few years [of the initial discovery],” Warren et al., write. “And because the initial searches were in the wrong direction, it is conceivable that the meteorite was missed and remains hidden in the high dunes, still waiting to be discovered.”

But what if Ripert was mistaken? A study in 2010 concluded his meteorite portion, which now resides in the US’s National Museum of Natural History, was broken from a parent body no bigger than 1.6 meters (5.25 feet), which goes against his claim. And yet, he described the presence of metallic needles that were too ductile for him to get a sample by trying to chisel them off. Nickel-rich structures that are similarly ductile were confirmed in iron meteorites in 2003 but were unknown to science in 1916.

The researchers are certain that magnetic data will solve the mystery – and yet if a large meteorite does not exist under the sand, Ripert still collected a sample of a meteorite from somewhere and appeared to describe meteorite ductile needles that wouldn’t be confirmed for another 87 years.

“[A]aeromagnetics data in the region south of Chinguetti… can finally resolve the question of the existence of the Chinguetti meteorite in a definitive manner,” they concluded. “If the result is negative the explanation of Ripert’s story would remain unsolved, however, and the problems of the ductile needles, and the coincidental discovery of the mesosiderite would remain.”

The study is available on the pre-print server ArXiv.