The world is building three gigantic optical telescopes whose size will dwarf anything we have today. It is hoped these three collectively will answer some of the big questions of the universe that have proven beyond existing instruments. However, a proposed National Science Foundation (NSF) budget cap puts one leg of the stool in danger.

Despite the ongoing wonders the JWST has revealed, the future of astronomy is not in space alone. We can build much bigger telescopes on the ground than we currently can in space, and it’s also much easier to fix, maintain, and upgrade them here. Plans for a telescope on the Moon with an accompanying base are far in the future.

The projects in which astronomers rest their medium-term hopes are the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), along with those like the Square Kilometer Array that operate at wavelengths far beyond the human eye (confusingly, all three are sometimes referred to as Extremely Large Telescopes, not just the ELT). Even with the atmosphere in the way, each would offer resolution far sharper than the JWST.

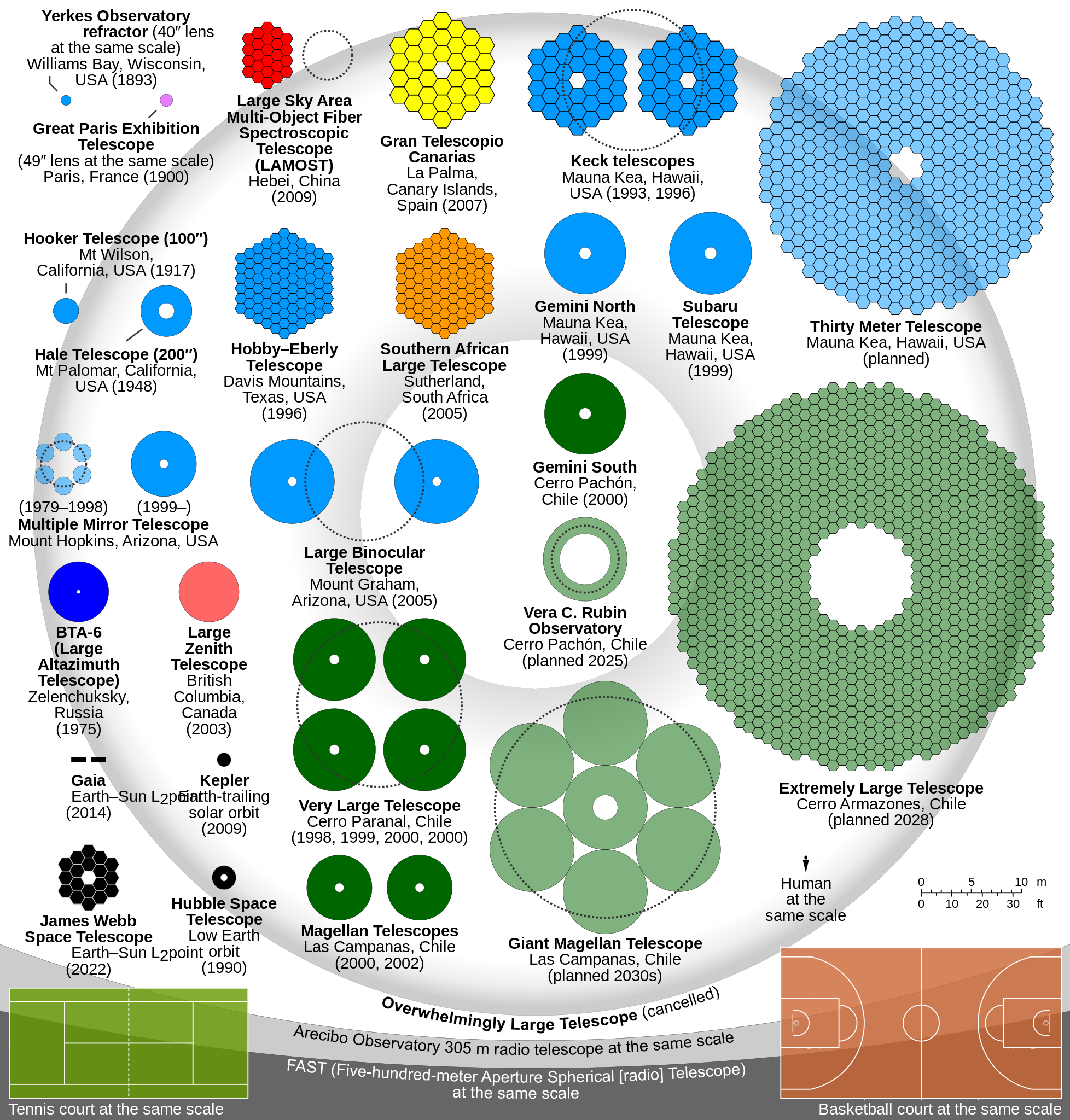

A comparison of existing and proposed telescopes shows just how much larger the big three will be than anything currently operating.

However, a new proposal would scrap one of the first two.

Astronomy is so collaborative many may not care who will build and own them, but the TMT and GMT are to be American-led, while the third is a collaboration of European and South American countries. That gives the ELT a level of insurance against budget cuts. None of the consortium partners want to look bad in front of the others by going back on their commitments. Work on the ELT started in 2017. It takes a long time to build something so enormous that also needs to be so precise, so first light is not expected to occur until 2028. Even if there are delays, there are few doubts it will happen eventually.

The TMT and the GMT, however, are both American projects, even if the latter will be based in Chile. Funding for the GMT is primarily from the USA’s NSF via a slate of universities and scientific institutions, even if six other countries are contributing. The TMT is an even more American project, despite Indian, Japanese, and Canadian involvement; it was initiated by two California universities and planned to be based in Hawaii.

However, the National Science Board, which advises the NSF, has proposed a $1.6 billion cap on NSF funding for giant telescopes. That’s less than either of the two are projected to cost on their own, although allowing for the other contributors, it should just about be adequate for one.

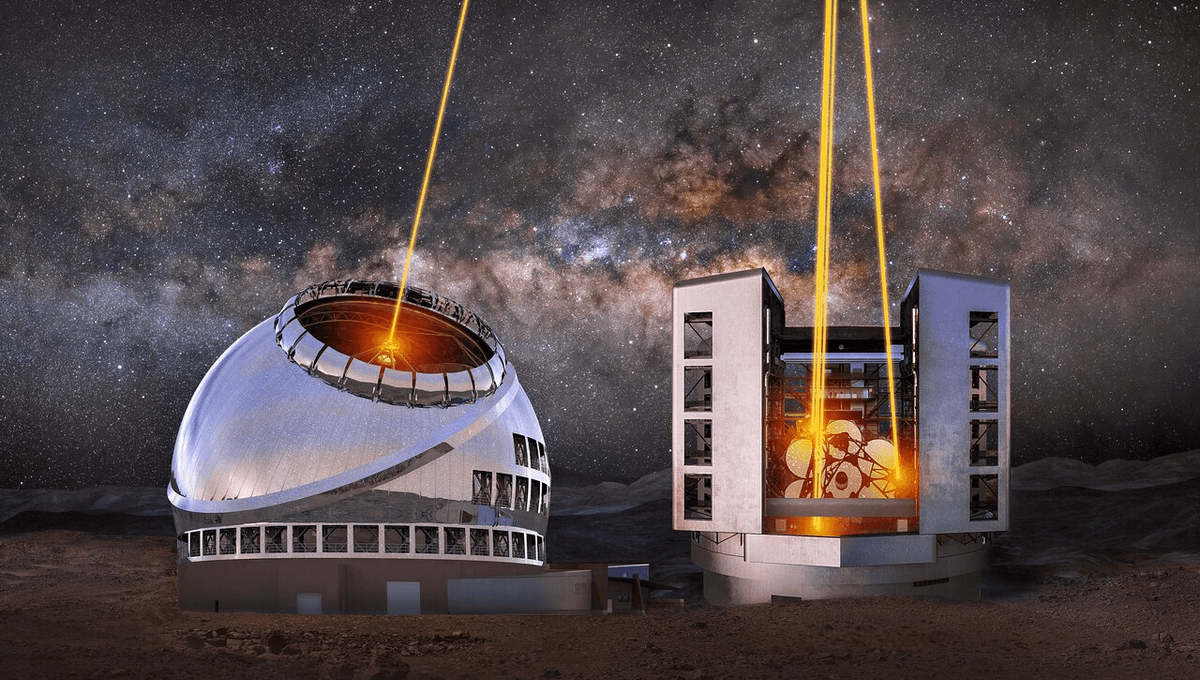

An artistic rendering of how the Grand Magellan Telescope may look, if it is ever built.

Image credit: GMTP Corporation

The statement issued by the Board makes clear they are not simply seeking to defer the costs, going slow until more funding comes along. Instead, it includes the recommendation: “NSF discuss with the Board during the May 2024 meeting its plan to select which of the two candidate telescopes the Agency plans to continue to support, including estimated costs and a timeline for the project.”

It’s possible the NSF could reject the recommendation, or indeed that Congress could decide to tip an extra billion and a half into astronomy because they think it’s so important. So far, that is what representatives of each team are banking on, at least publicly, rather than squabbling over who should take priority. You wouldn’t want to bet on new money arriving, however, even if we weren’t in an era where the government is hamstrung by partisan fighting that makes any budget allocation difficult.

Theoretically, other contributors could increase their shares, but John O’Meara, chief scientist at Keck Observatory, told Space.com: “To my knowledge, neither telescope today has a path forward without the investment by NSF.”

Astronomers have been expressing their distress, and emphasizing why both are needed.

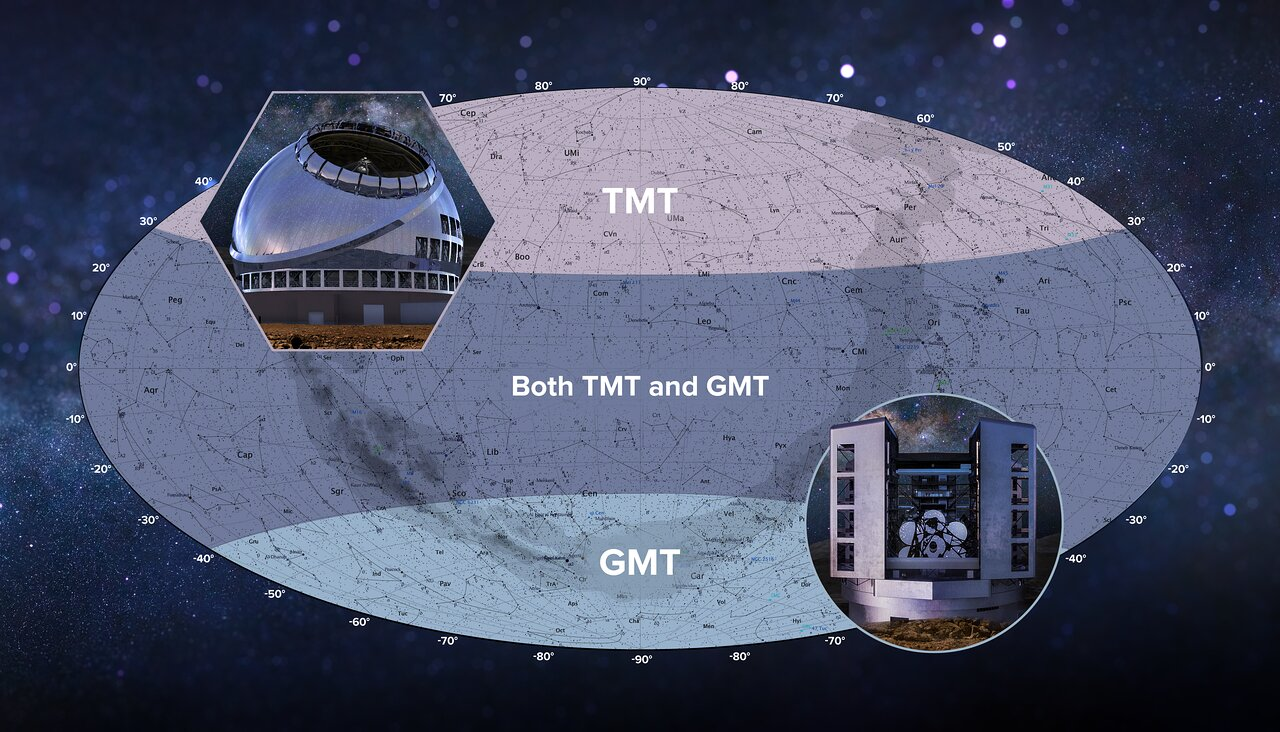

Those associated with other areas of science may have little sympathy; perhaps quietly mocking those who thought they’d get two shiny new toys and have to settle for one. However, the two instruments have been specifically designed to work together. No location on Earth can see the entire sky; only having one instrument in the Northern Hemisphere and one in the Southern offers complete coverage. Each has been designed to maximize certain capacities on the assumption the other will take up the slack in other areas.

Areas of the sky that could be seen by the proposed Giant Magellan Telescope and Thirty Meter Telescope. Without one of them, much of the sky will be uncovered.

Image credit: US-ELTP (TIO/NOIRLab/GMTO)

At first sight, the TMT would appear the logical survivor. Being in the Northern Hemisphere, it can tag team with the ELT, and a proposed US location could offer a constituency to lobby for it.

However, the TMT is so strongly opposed by Native Hawaiians that consideration has been given to moving it to the Canary Islands – still in the north, but part of Spain. Moreover, dumping either would mean letting almost all the money spent so far go to waste, and that’s a lot more on the GMT, which is much further advanced, than the TMT.

Most people can think of plenty of other worthy uses for $1.5 billion, whether it be in medical research to cure diseases, other forms of science focused on global crises, or outside science entirely. On the other hand, basic research has a long history of paying for itself in ways that were quite unexpected at the time. Building both telescopes would mean an extra $5 in taxes per American, not per year, but as a once-off. Their combined cost will be far less than the JWST, and each will last much longer.

Allocating budgets is always hard, and gets harder still when comparing benefits that are likely to be so different – in this case, knowledge for knowledge’s sake set against options with clear practical, albeit uncertain, payoffs. Compared to that, the NSF may decide that choosing between two instruments with different, but overlapping, capacities is relatively easy.