The Earth’s geological timeline is an essential tool for understanding how it has changed, and planetary scientists have sought to replicate it for planets and moons we have explored. However, the existing timeline for the Moon was created when we knew a lot less about its history, and is increasingly dated. A new effort attempts to offer a timeline that makes more sense.

The Earth’s timeline reflects the fact that various catastrophic events can be found in the geological record, and these are used to mark out units of geological time. In some cases the definitions are easy, such as the layer of material dividing the Cretaceous from the Paleogene. Others are more contentious, as seen in the ongoing controversy about when to define the start of the Anthropocene, if we eventually acknowledge it as a geological epoch at all.

The Moon requires something a bit different. On Earth, biological changes are as important as geological ones when it comes to defining boundaries in time, something that is naturally not available on the Moon. A lunar timeline was proposed before we even visited our satellite, and refined using the Apollo results, but some of what we have learned since has made it outdated. In particular, it ignores the more ancient far side almost entirely, and makes no allowance for what we have now learned about the Moon’s early years.

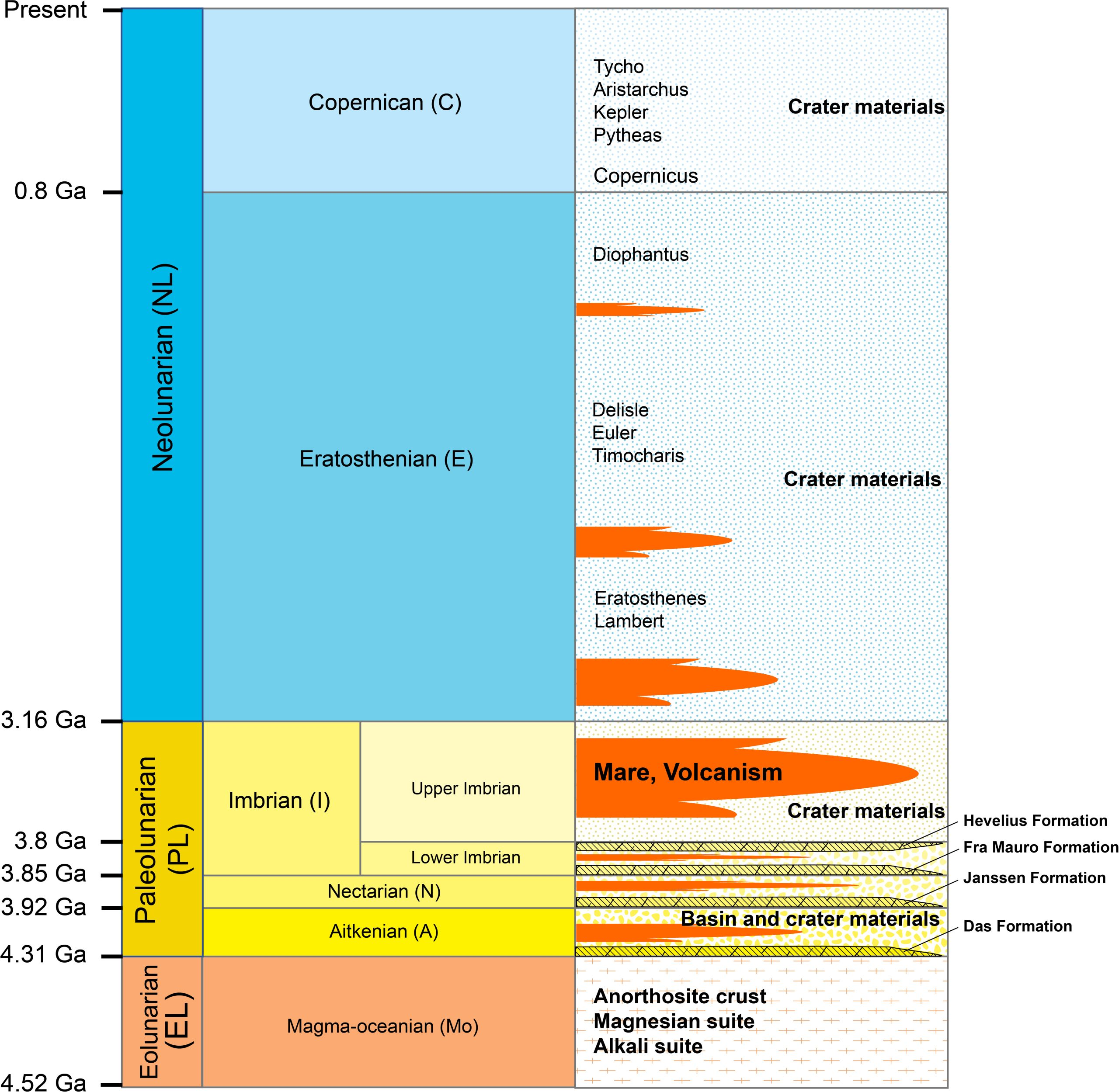

Consequently, a team of authors mostly from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have proposed an update, dividing the Moon’s timeline into three eons and six periods.

The proposal is based around the observation that the Moon had very hot origins that dominated its early development, but as time went on these faded leaving the Moon to the whims of the wider universe.

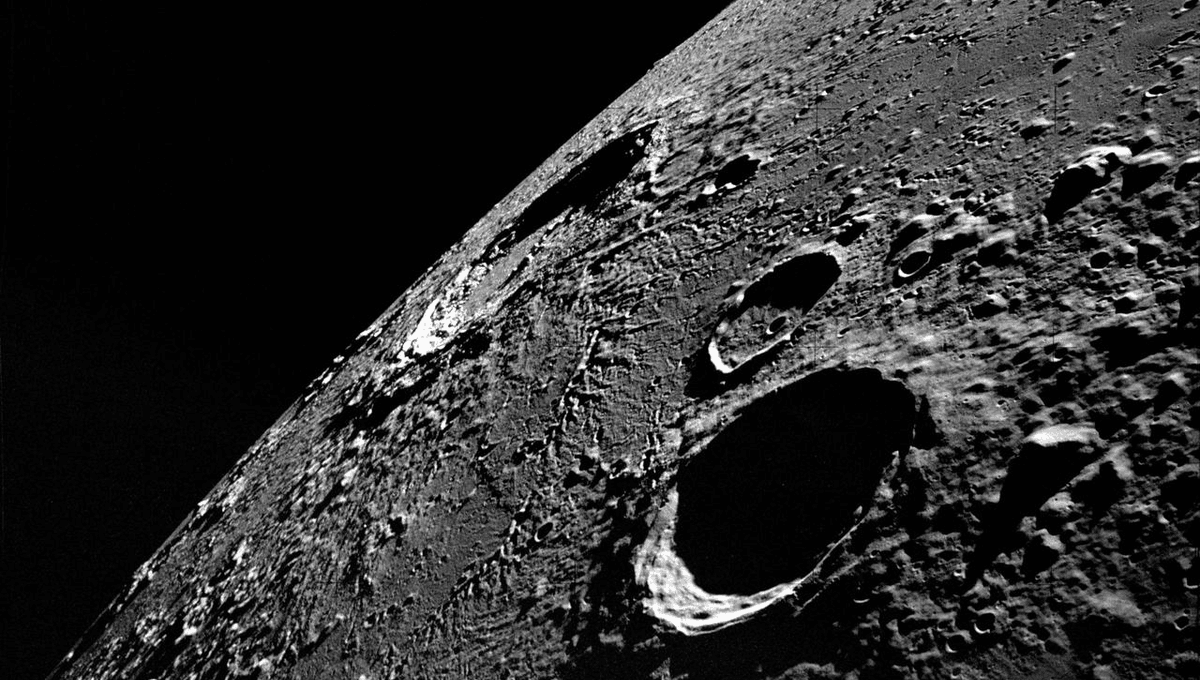

What the authors call the Eolunarian Eon is the time in which changes on the Moon were primarily driven by internal forces. The extreme heat produced by the Moon’s formation created a magma ocean that slowly solidified into primary crust. Large objects slammed into the Moon, but left no permanent marks thanks to its near-liquid status.

The Paleolunarian Eon took place while internal and external processes were of similar significance – both were dying down, but the supply of asteroids was falling far more slowly than the internal heat sources. Major formations survive from this era, beginning with the Das Formation formed from ejecta near the South Pole by the creation of the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) Basin. Not only is the SPA Basin now considered the largest and oldest impact structure on the Moon, but it is likely to be the site of the first lunar bases, giving its unique terrain a double significance.

The Neolunarian Eon took place once volcanic activity had largely ceased and most change was coming from without. Although Chang’e 5 proved volcanic activity lasted until at least 2 billion years ago, such events were rare by then and overwhelmed by asteroid strikes, so the authors choose not to make the last eruption the dividing line between eons.

Instead, the authors date the boundaries between the eons as 4.31 and 3.16 billion years ago.

The proposed new lunar timeline’s (from left) dates, eons, periods, and significant events.

Image credit: Science China Press

Just as the Earth’s four great eons are divided into finer eras, periods and epochs, the authors propose the two most recent eons should have subdivisions.

They call the current period the Copernican, dating from 800,000 million years ago when the prominent crater Copernicus was formed. The earlier part of the Neolunarian has been named the Eratosthenian after one of the oldest surviving craters. The proposal does not include the suggestion that the Moon should now be considered to be in its own Anthropocene.

The Paleolunarian has three periods: the Imbrian, during which most of the large seas were formed, and earlier brief (by lunar standards) Nectarian and Aitkenian Periods; these lasted just 70 and 390 million years respectively.

Whether the majority of lunar scientists will adopt this timeline, modify it, or choose something else entirely remains to be seen, but if as the race for the Moon hots up, a good timeline will be much in demand.

The study is published in the journal Science China Earth Sciences.