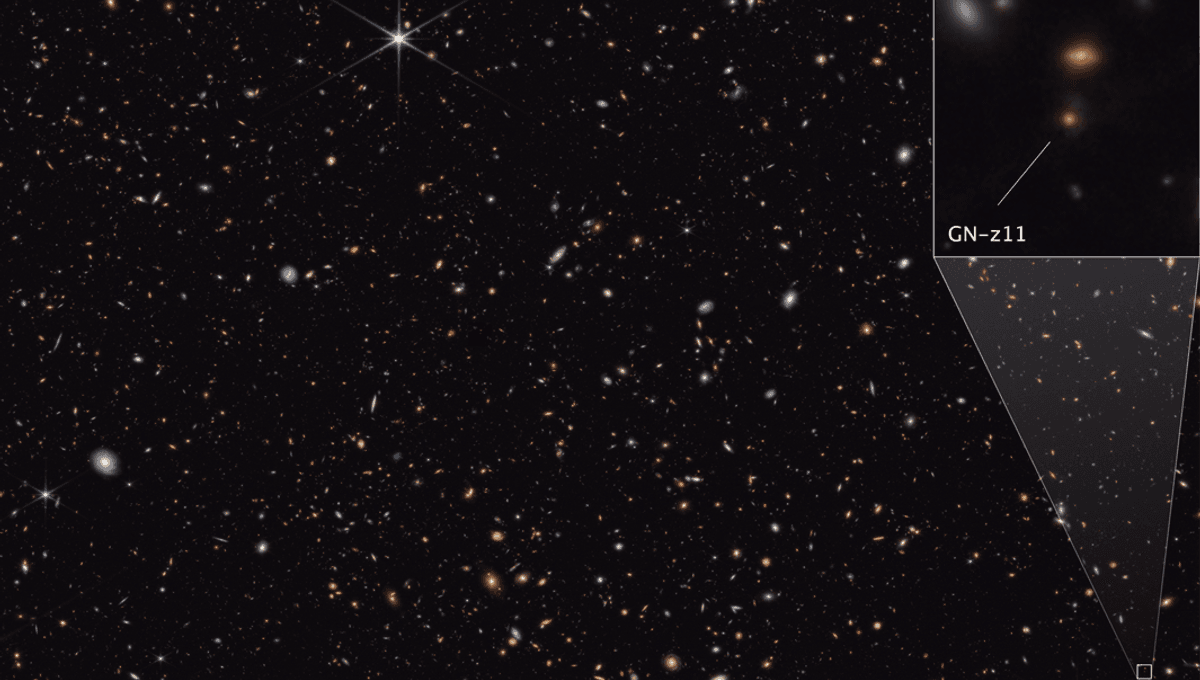

The JWST’s observations of the galaxy GN-z11 have revealed a clump of helium in the galactic halo that may contain the much-sought first generation of stars.

Stars like the Sun contain metals only forged in the last stages of stellar life. These elements come from previous generations of stars that produced these heavier elements as their parting gift to the universe. The Sun is called a Population I star, while its immediate predecessors containing lower metal ratios are known as Population II. Some Population II stars can be seen by looking far back in time or finding low mass stars that age slowly.

For a long time one of the priorities of astronomy has been to try to find Population III stars, those that have no predecessors and formed instead from pristine material left behind by the Big Bang. We’ve yet to do this, but may now be getting close.

For seven years GN-z11 was the most distant galaxy known, having been found by the Hubble space telescope and its distance identified in 2015. The JWST took away that crown – but it has given a lot back to GN-z11’s status, revealing the earliest supermassive black hole ever found and nitrogen left behind by so-called “celestial monster” stars 5,000-10,000 times the mass of the Sun.

Since the greater mass a star has, the shorter its lifespan, there’s only a short window to catch such an object while it is active. One step on the road is to identify places where pristine gas, from which Population III stars might form, can be found – and this is what the JWST may now have done.

A team led by Professor Roberto Maiolino found a clump of helium in GN-z11’s halo using the JWST’s Near-infrared Spectrograph.

“The fact that we don’t see anything else beyond helium suggests that this clump must be fairly pristine,” Maiolino said in a statement. “This is something that was expected by theory and simulations in the vicinity of particularly massive galaxies from these epochs — that there should be pockets of pristine gas surviving in the halo, and these may collapse and form Population III star clusters.”

Indeed, Maiolino thinks Population III stars we have not seen directly may be what are lighting up this gas, something hinted by the width of the doubly ionized emission line in the spectrum.

Although stars are far brighter than patches of gas lit up second hand, they’re also vastly smaller. We’re seeing GN-z11 as it was just 400 million years after the universe formed, and the immense distances involved make clusters of stars, let alone individual objects, exceptionally hard to resolve. Nevertheless, the JWST is scheduled to spend even longer on this crucial galaxy, building up higher-resolution images. Now they know where to look, Maiolino and colleagues hope to use those deeper observations to find stars newly emerged within pristine patches like the one they identified.

If the team are right, we’re in for a treat, with hints the heaviest of the stars they are chasing have masses of at least 500 times that of the Sun. These may not match the “celestial monsters” whose nitrogen legacy was spotted, but they’d be more massive than any stars in our own galaxy, or anything nearby. Collectively, they expect this initial cluster to be releasing around 20 billion times as much light as the Sun.

A report on the discovery has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, and can be seen on ArXiv.org.