A cluster of faint, red dots lurking in the farthest reaches of the universe could change our understanding of how supermassive black holes (SMBHs) form.

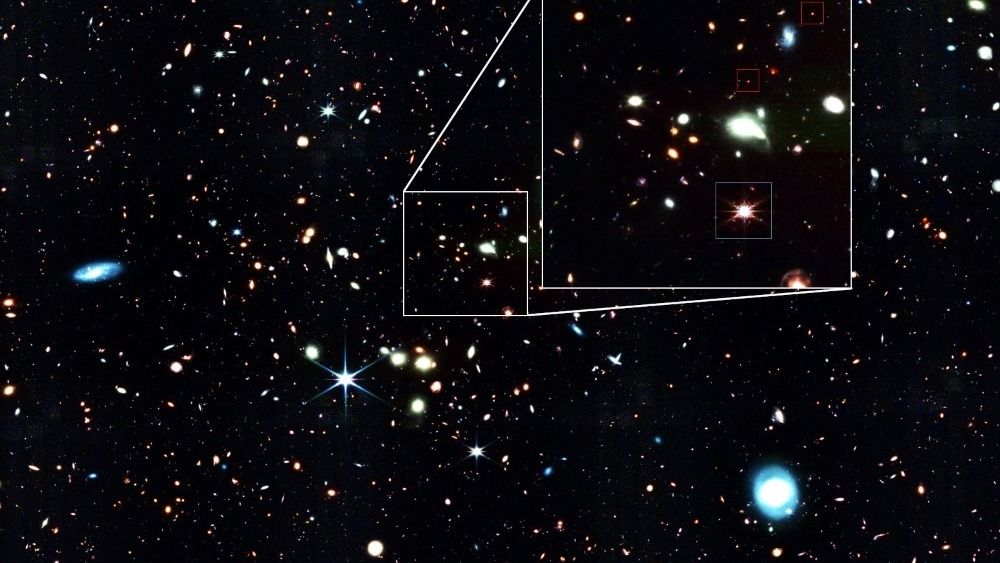

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) coincidentally spotted the specks, which astronomers say are actually “baby quasars,” while studying an unrelated faraway quasar called J1148+5251.

Quasars are extremely bright objects powered by actively feeding supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. The target quasar emitted its light approximately 13 billion years ago — less than a billion years after the Big Bang, according to a study published Thursday (March 7) in The Astrophysical Journal.

While these mysterious spots had been previously recorded by the Hubble Space Telescope, it wasn’t until scientists viewed them using the far more powerful JWST that they could finally distinguish them from normal galaxies, according to a statement.

“The JWST helped us determine that faint little red dots … are small versions of extremely massive black holes,” lead study author Jorryt Matthee, an assistant professor of astrophysics at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, said in the statement. “These special objects could change the way we think about the genesis of black holes.”

Related: 8 stunning James Webb Space Telescope discoveries made in 2023

Analyzing these tiny dots, which are tinged red by clouds of dust obscuring their light, required JWST’s powerful infrared camera. By studying the different wavelengths of light emitted by the dots, the researchers determined that each one appeared to be a “very small gas cloud that moves extremely rapidly and orbits something very massive like an SMBH,” Matthee said. In other words — a young quasar.

The dots don’t seem out of place in the early universe, but they may be growing into “problematic quasars” — ultra-monstrous black holes that appear too massive to exist at such early epochs of the universe, the researchers said.

Astronomers using JWST have already uncovered many of these problematic black holes and struggle to explain them with current theories of cosmology.

“If we consider that quasars originate from the explosions of massive stars — and that we know their maximum growth rate from the general laws of physics, some of them look like they have grown faster than is possible,” Matthee said. “It’s like looking at a five-year-old child that is two meters [6.5 feet] tall. Something doesn’t add up.”

The researchers hope further study of these newly discovered “baby quasars” could help reveal how these problematic black holes grow so big, so fast.

“Studying baby versions of the overly massive SMBHs in more detail will allow us to better understand how problematic quasars come to exist,” Matthee said.